We are used to reading Prabhupada’s books and accepting the translations he gives as authoritative, and we may automatically do the same when reading books from other authors, accepting and quoting whatever they translate, but this is quite dangerous.

The point about “translations” of Sanskrit works is that they are rarely translations, but more like interpretations. Understanding the scriptures demands making assumptions about the meaning of the words and the way they relate to each other, and thus the same verse can be translated in many different ways.

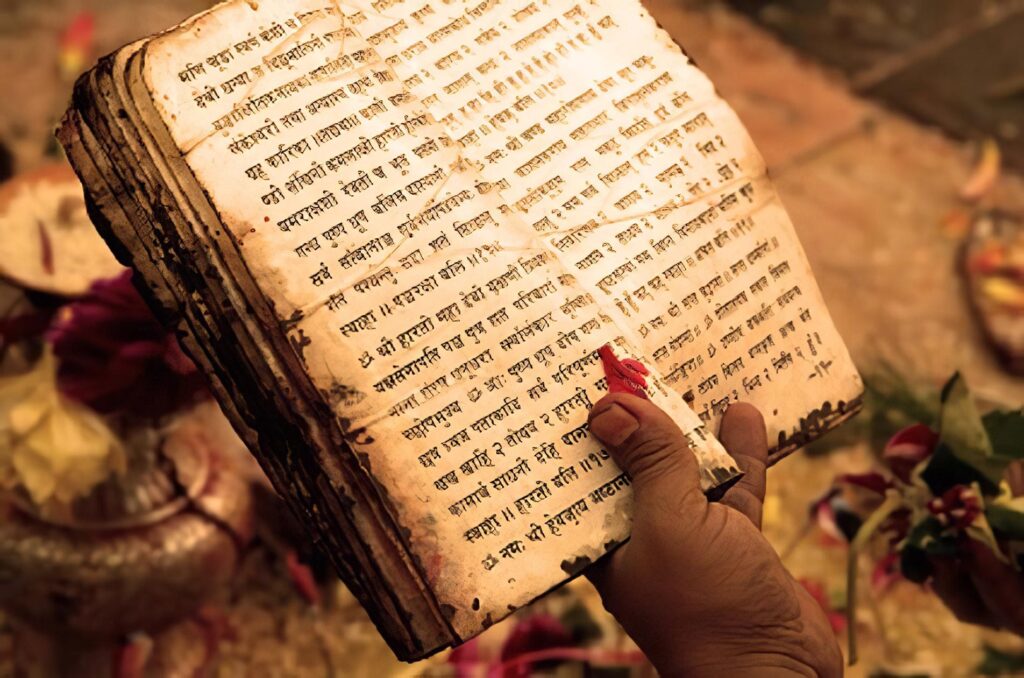

Take for exemple verse 8.14.1 from the Chāndogya Upaniṣad:

ākāśo ha vai nāma-rūpayor nirvahitā te yad antarā tad brahma tad amṛtaṁ sa ātmā

It can be translated as:

“Sky is the creator of names and forms. That sky within is expanded without limit. That sky is eternal. That sky is the Self.”

The main word in this verse is “akasa”, which means “sky” or “ether” (the subtle material element). However, we can see that in this verse it doesn’t seem to make much sense. Sky or ether is an inanimate material element, so how can be the creator of names and forms? How can it be the self?

It’s clear that in this verse the word “akasa” describes something else. Srila Baladeva Vidyabhushana explains that it refers to the Lord in the form of Supersoul. He is the creator of names and forms (since He created the universe), He is eternal and unlimited and He is the Supreme Self.

Following this interpretation, the verse could be translated as:

“The Lord is the creator of names and forms. As Paramatma, He is within and without, and expands without limit. The Lord is eternal, He is the Supreme Self.

However, this verse could be interpreted in different ways.

One could argue that the akasa described in this verse is the jiva after attaining liberation from material bondage. He could point to the words “yad antarā” (which is within) as referring to the jiva after attaining liberation, becoming free from all names and forms.

Following this interpretation, one could argue that the words “nāma-rūpayor nirvahitā” (the creator of names and forms) apply to the jiva in his conditioned state, when under material dualities, that the world “akasa” means “effulgence” and that the words “tad brahma tad amṛtam” (that spirit which is immortal) describe the qualities of the jiva after attaining liberation.

Making these assumptions, the verse could be translated as something like:

“That effulgence that is within, the creator of names and forms, that spirit that is immortal, is the self.”

You can see that following this interpretation the meaning of the verse completely changes. Now, instead of describing the Lord the verse appears to describe the individual soul inside the body, who will eventually merge into the Supreme Brahman after attaining perfection.

One popular translation gives also a similar interpretation, reading: “The sky is the space beyond name and form. That which is within is Brahman, that which is immortal, that is the Self.”

Most translations available in the market, including many translations of Gaudiya Vaishnava books have similar problems. Consciously or unconsciously the author gives meanings for the verses following his personal understanding of it, which often doesn’t reflect the conclusions of previous acaryas.

Sanskrit verses must be interpreted according to other verses of the passage and the general conclusions of the scriptures, which in turn must be carefully received from the proper disciplic succession. Without this, one will most probably come to the wrong meaning and will mislead others who are following his interpretation. Whe should thus be very careful with what we read.

According to Srila Baladeva Vidyabhushana, the Vedanta Sutra 1.3.41 explains the correct interpretation of the Chāndogya Upaniṣad 8.14.1: ākāśo’rthāntaratvādi-vyapadeśāt

According to this sutra, the word “akasa” used here refers to the Supreme Personality of Godhead (in his form as Paramatma) because the akasa (sky) described here is different from the liberated jiva, being unlimited and all-pervading.

Again, the correct interpretation of the verse takes into account a very important conclusion of the scriptures: The Lord is great and the jiva is very small. When this conclusion is accepted, it becomes easier to understand when verses speak about the Lord, because in these passages the Lord is always describe as unlimited, all-pervading, the creator, and so on.

For example, the word “nirvahitā” used in the verses refers to the creator of names and forms. This can’t be applied to the jiva, because in the conditioned state, the jiva accepts material names and forms (different material bodies) under the influence of Karma, and in the liberated state the jiva gives up all material names and forms altogueter. In this way, the only one who creates names and forms at any stage is the Lord.

This is corroborated in the Chandogya Upanisad (6.3.2), where is mentioned: anena jivenatmananupravicya nama-rupe vyakaravani (With the jivas I will now enter the material world. Now I will create a variety of names and forms).

The word ādi in the sutra (beginning with) indicates that there are also other reasons. The world “Brahman” in the verse (great without limit) can’t be used to describe the jiva (even in the liberated stage) but it can be very naturally used to describe the Supreme Lord. Similarly, the word “akasa” in the way it’s used in this verse, meaning all-pervading, is applicable to the Lord in His form as Paramatma, but not to the jiva.

By all these arguments, it’s proved that verse 8.14.1 from the Chāndogya Upaniṣad speaks about the Lord, and not the jiva, who can’t attain the qualities mentioned in the verse even in the liberated stage.