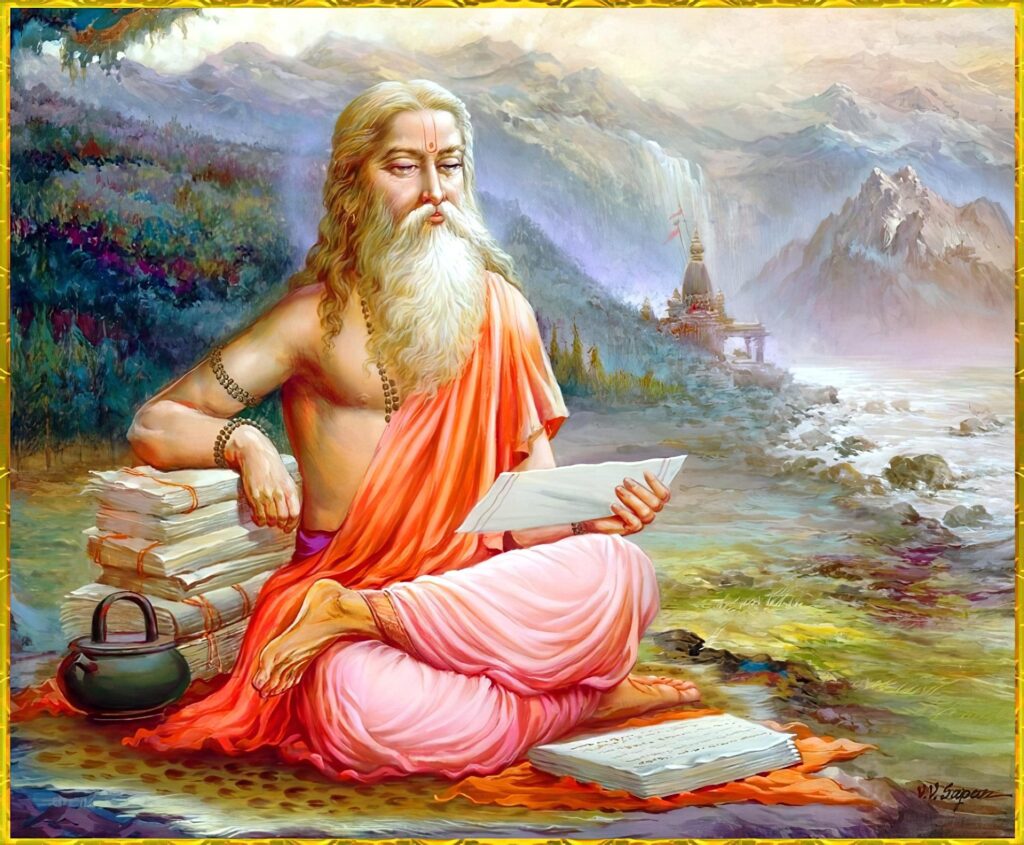

Vyasadeva did a monumental work in compiling the Vedic literature. All the Vedic texts we have today, including all the Puranas, Upanishads, and so on are estimated to be just 7% of all the verses compiled by Vyasadeva that survived the passage of time. Originally he wrote much more.

Vyasadeva originally divided the original Veda into four and passed each division to one of his disciples. They in turn subdivided the knowledge amongst their different disciples, giving birth to all different branches of knowledge:

1) Ṛg Veda (given to Paila Ṛṣi)

2) Sāma Veda (given to Jaimini)

3) Yajur Veda (given to Vaiśampāyana)

4) Atharva Veda (given to Aṅgirā)

Srila Prabhupada mentions that “The original source of knowledge is the Vedas. There are no branches of knowledge, either mundane or transcendental, which do not belong to the original text of the Vedas. They have simply been developed into different branches.”

The Vedas include both spiritual and material knowledge and all branches of human knowledge, including sciences like medicine, mathematics, chemistry, astronomy, physics, etc. came from these different branches started by the disciples of Vyasadeva. As time went on, however, these different branches of knowledge lost the original connection with the Vedas and thus lost their spiritual touch.

Because the Vedas deal mainly with material piety, fruitive activities and different branches of material knowledge, the real purport of the Vedas (which is spiritual knowledge) is not always evident. To make it more clear, Vyasadeva then compiled the 108 Upanisads selecting only the most relevant philosophical passages, and compiled their conclusions in the Vedanta Sutra.

Next, Vyasadeva compiled the 5th Veda in the form of the Puranas and Itihasas, which describe the Vedic knowledge in the form of stories that are easier to understand than the heavy philosophy of the four original Vedas. They were given to Romaharsana. Later, when he was killed by Lord Balarama for his ofense, the custody was passed to Suta Goswami.

All the Vedas were originally spoken by Lord Brahma, who received this knowledge directly from Krsna. In his Tattva Sandarbha. Srila Jiva Goswami describes that Brahma originally spoke the Puranas with one billion verses. In other words, the Puranas were originally much more extensive than the books we have access to nowadays. This original version of one billion verses is still studied on the celestial planets, but understanding the situation of people of this age, Srila Vyasadeva selected the most essential passages.

It’s interesting to note that all Puranas deal with the same ten subjects:

1) Sarga (the primary creation done by Lord Maha-Vishnu).

2) Visarga (the secondary creation, done by Lord Brahma).

3) Vrtti (the maintenance of the universe, conducted by different demigods empowered by the Lord).

4) Raksa (the maintenance of all living beings who live inside the universe).

5) Antarani (the reigns of the Manus, 14 of which appear during each day of Brahma).

6) Vamsah (the description of the dynasties of great kings and their descendants).

7) Vamsa-anucaritam (the narrations of their activities and the spiritual messages they contain).

8) Samstha (the annihilation of the universe at the end of each day of Brahma and at the end of his life)

9) Hetuh (the reasons and motivation for the involvement of the soul in material activities)

10) Apasrayah (description of the supreme shelter, the Lord)

The same pastimes and historical events are explained in all the different Puranas, but each Purana focuses on different details. This happens because all the Puranas came from a single narration (the original Purana of one billion verses) which was divided by Srila Vyasadeva into 18 books for different classes of readers, classified according to the three modes of material nature.

a) For people in the mode of ignorance, there are the Shiva, Linga, Matsya, Kurma, Skanda, and Agni Puranas, who often recommend the worship of demigods with the goal of gradually elevating the reader to a pious platform. To reinforce the faith of the reader, demigods like Lord Shiva are glorified up to the point one may think they are supreme.

b) For people in the mode of passion, there are the Brahma, Brahmanda, Brahmavaivarta, Markandeya, Bhavisya, and Vamana Puranas, which often emphasize fruitive activities mixed with spiritual knowledge, offering rewards to the reader in exchange for spiritual practice.

c) Finally, for readers in the mode of Goodness, there are the Vishnu, Bhagavata, Garuda, Naradiya, Padma, and Varaha Puranas, which directly speak about devotional service to the Lord.

All the Puranas, including the ones for people in the mode of ignorance, contain spiritual knowledge (we can see that Prabhupada often quotes from the Skanda Purana, for example, which is one of the Puranas for people in the mode of ignorance), it’s just that the Puranas in the mode of ignorance and passion also discuss other topics that are necessary to attract the attention of readers in the lower modes, while the sattvic puranas, especially the Srimad Bhagavam discuss directly devotional service. Right in the opening verses of the Srimad Bhagavatam, Vyasadeva declares that everything that is not connected with pure love to Krsna is excluded from Srimad Bhagavatam.

The 4th chapter of the first canto of Srimad Bhagavatam brings us a short narration of this exhaustive work of Srila Vyasadeva in compiling all the Vedic literature, culminating with the Srimad Bhagavatam. Why did Vyasadeva take the trouble of writing such a vast literature?

“The great sage, who was fully equipped in knowledge, could see through his transcendental vision the deterioration of everything material due to the influence of the age. He could also see that the faithless people in general would be reduced in duration of life and would be impatient due to lack of goodness. Thus he contemplated for the welfare of men in all statuses and orders of life.” (SB 1.4.17-18)

Vyasadeva did all this work out of compassion for the people of Kali-yuga, who otherwise would not be able to understand the Vedas. He also compiled the Mahabharata, using the history of the Pandavas as a pretext to transmit transcendental knowledge in a format that could be easily assimilated by the less educated parcels of the population. Until today it’s common that children in India grow up hearing stories from the Mahabharata, and thus become familiar with the principles of dharma, even if their parents are materialists.