Astanga-yoga is recommended in several places of the scriptures as a process to allow ones who are not ready to practice the path of devotional service to gradually achieve transcendental realization. Vidhura recommended it to Dritarastra after he retired from the palace, for example, understanding that after committing so many offenses during his life, he would not be able to adopt the process of Bhakti.

Nowadays there is a great interest in yoga, but with so many fashionable styles and the almost universal goals of controlling stress and toning the body, the essence of the yoga process is lost, to the point that most simply relate the word “yoga” with physical exercises.

The original process of transcendental meditation is called Astanga-yoga, or the eight-fold yoga system (asta means “eight” and anga means “limbs” in Sanskrit), it consists of eight levels of practice: Yama, Niyama, Asana, Pranayama, Pratyahara, Dharana, Dhyana and Samadhi. This is the process mentioned in the Bhagavad-Gita and other scriptures, which was practiced by yogis and transcendentalists through the ages. All the modern processes of yoga derive from this original eight-fold system, but in most cases important parts of the process are lost, discarded, or modified.

The Astanga-Yoga process starts with Yama and Niyama. Yama means “to do” and Niyama “not to do”. These are rules and regulations, or prescriptions and prohibitions that one is supposed to follow as part of his practice.

Yama means items that are favorable to the spiritual practice and therefore should be practiced, and Niyama means what is unfavorable and should thus be avoided or abandoned. For example, in the Bhagavad-Gita Krsna mentions that “There is no possibility of one’s becoming a yogī, O Arjuna, if one eats too much or eats too little, sleeps too much or does not sleep enough.” (Bg 6.16). This is an example of yama/niyama.

Similarly, other prescriptions include to wake-up early in the morning, not going to sleep too late, following a vegetarian diet, being non-violent, maintaining a good standard of cleanliness and sense-control, etc. Most rules and prohibitions of yama/niyama are useful for all spiritual seekers, not only to astanga-yogis.

The third component is Asana, which consists of bodily exercises and sitting postures. The asanas help one to ascend from a gross material platform to a more subtle platform, calming the mind and helping to develop concentration, which are prerequisites for the more advanced stages of the process. The asanas are thus a preparation, just like a runner may warm up and execute other routines as a preparation for his training.

In other words, asanas means to use the material body to perform activities that can elevate one’s consciousness. In this sense, there are similarities with the process of Karma-yoga described in the Bhagavad-gita. In the case of the Astanga-yoga process, the asanas also help to prepare the body for standing in the same position for the long times required in the practice of meditation.

More advanced than bodily postures is the process of Pranayama, which consists of breathing exercises: inhaling, exhaling, and holding the breath. It’s a more subtle form of the process of employing the gross body in actions that help to elevate one’s consciousness.

The Pranayama process is summarily explained in the Bhagavad-Gita (4.29):

“Still others, who are inclined to the process of breath restraint to remain in trance, practice by offering the movement of the outgoing breath into the incoming, and the incoming breath into the outgoing, and thus at last remain in trance, stopping all breathing. Others, curtailing the eating process, offer the outgoing breath into itself as a sacrifice.”

Just like the asanas, the purpose of the pranayama process is to stop the mind and senses from engaging in materialistic activities. In both cases, the goal is not to make the body and mind stronger in order to be able to work more, or simply to manage stress, but to advance in spiritual practice. The problem with the way most people practice yoga nowadays is exactly that, because of a lack of a broader understanding of the process and its goals, most people practice isolated parts of the process with the goal of simply improving their physical endurance or mental alertness, and thus they are just like someone that licks the external part of a pot of honey instead of tasting what is inside.

The next step is the process of Pratyahara, which means to control the mind and senses. In the Bhagavad-gita, the material body is compared with a chariot, where the senses are the horses, the mind and intelligence are the reins and coachman, and the soul is the passenger. When one starts the meditation process, the mind will wander everywhere, bringing to consciousness a series of remembrances, desires, plans, feelings, etc. Pratyahara means to withdraw the mind and focus it in the practice of yoga or, in other words, to withdraw the senses from matter and engage them in transcendence, just like in the example of the tortoise, that can withdraw his members when necessary, and again expand them when desired.

Without mastering the process of pratyahara, it’s not possible for one to successfully practice the next level (dharana, or meditation). Nowadays, many try to meditate, but without pratyahara, it’s not possible to successfully do that. This leads to many concocted processes of guided meditation that just make one meditate in different aspects of material life instead of proper dharana. This way, the practice becomes a dead-end, that doesn’t lead anywhere.

This stage is also explained in the Bhagavad-Gita: “One has to drive out the sense objects such as sound, touch, form, taste and smell by the pratyāhāra process in yoga, and then keep the vision of the eyes between the two eyebrows and concentrate on the tip of the nose with half-closed lids. There is no benefit in closing the eyes altogether, because then there is every chance of falling asleep. Nor is there benefit in opening the eyes completely, because then there is the hazard of being attracted by sense objects. The breathing movement is restrained within the nostrils by neutralizing the up-moving and down-moving air within the body. By practice of such yoga one is able to gain control over the senses, refrain from outward sense objects, and thus prepare oneself for liberation in the Supreme.” (BG 5.27-28 purport)

For a practitioner of bhakti-yoga, pratyahara means to engage oneself in practical devotional service, in this way the mind and senses are automatically controlled. This is explained in the Srimad Bhagavatam (3.33.8 purport): “Pratyāhāra means to wind up the activities of the senses. The level of realization of the Supreme Lord evidenced by Devahūti is possible when one is able to withdraw the senses from material activities. When one is engaged in devotional service, there is no scope for his senses to be engaged otherwise. In such full Kṛṣṇa consciousness, one can understand the Supreme Lord as He is.”

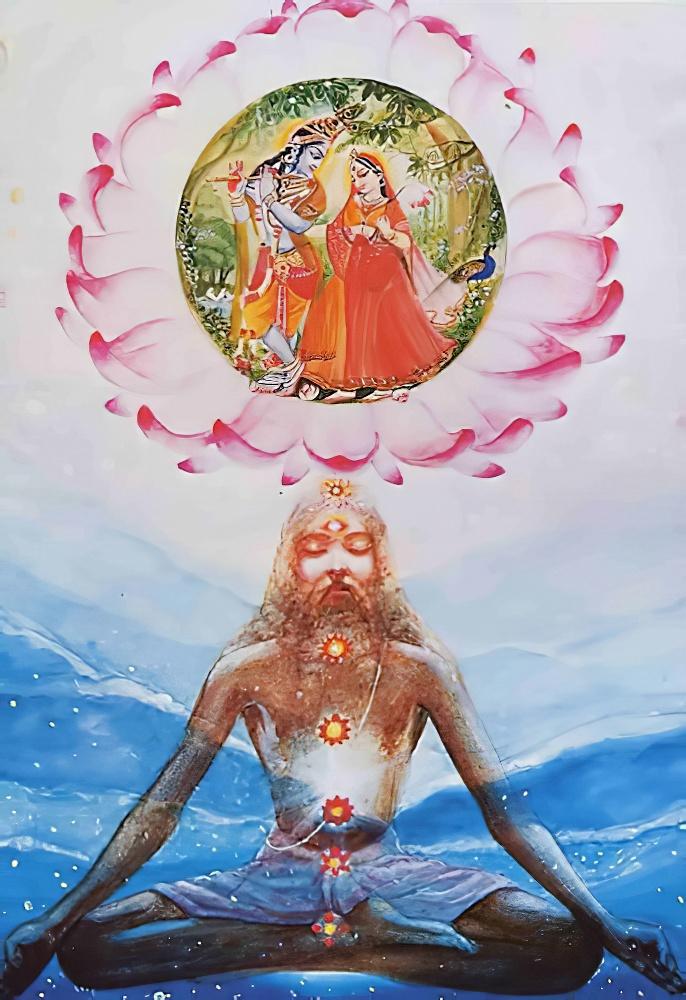

The next stage is called Dharana, or fixed meditation. Nowadays many have the idea that to meditate means to empty the mind of all thoughts. However, not only this is not recommended, but it is actually not even possible, since thoughts will always come to one’s mind. Instead, the Astanga-yoga process prescribes meditation in the form of the Lord. A yogi takes shelter (Asraya) in a particular form of the Lord and fixes his mind on all the details of this particular form. This fixed meditation is thus a form of worship.

The object of the meditation (Dharana-asraya) can be the Universal Form (virat-rupa) or the form of Paramatma inside the heart, according to the yogi’s level of advancement.

One who has material desires, or is in a gross level of consciousness is recommended to meditate in the Universal Form (as described in the second canto of Srimad Bhagavatam). In this process, one meditates in the different levels of planetary systems situated inside the universal form, and thus gradually elevates his consciousness, from the gross planets to the subtle planets, up to Brahmaloka, and then to the subtle coverings of the universe, ego, and mahat-tattva, up to the point of pure consciousness, or brahman realization (the stage of liberation). This is a process that can take several lives and involve taking birth in progressively higher planetary systems, where the yogi gradually improves his practice and consciousness until he achieves perfection. The upper planetary systems are full of souls that are executing this gradual ascending process.

This Universal Form is essentially an imaginary form, where different levels of planetary systems and different personalities and elements of the cosmic creation are taken as different parts and limbs of the Universal Form. In one sense, this is so, since the universe is the energy of the Lord, but in the other sense, it’s imaginary since the Lord doesn’t have a material form. To meditate on the universal form of the Lord is thus an indirect form of meditation that can help yogis that are too much absorbed in material consciousness, and thus can’t conceive anything beyond it. Such yogis can’t conceive the existence of the transcendental forms of the Lord, and thus meditation in the universal form is the only feasible process.

A yogi who is already free from material desire, situated in a more advanced stage, can skip meditation in the universal form and go straight to meditation in the Supersoul, the form of the Lord situated in one’s heart (also described in detail in the Srimad Bhagavatam), fixing his mind in all the details of the transcendental form of the Lord. This is a direct process that allows one to achieve perfection in this same life.

For a bhakti-yogi, the process of Dharana is achieved through the chanting of the maha-mantra, which provides a shelter for one’s meditation, allowing him to connect with the transcendental platform with much less effort.

The next stage is Dhyana. As the meditation intensifies and becomes deeper, a yogi enters the stage of Dhyana. Although both Dharana and Dhyana involve basically the same practice of meditation, Dharana is the beginning stage, whereas Dhyana is the advanced stage, when the yogi masters the process and starts to come close to the final goal.

Finally, we have the stage of Samadhi, A deep trance that is attained when the yogi attains perfection in the meditation process. In Samadhi the yogi is capable of fully situating his consciousness in the spiritual platform, attaining the level of brahma-bhuta (brahman realization, or liberation), which is the final goal of the process of yoga.

Samadhi is also the ultimate goal in the process of Bhakti-yoga, where it’s also attained through fixed meditation. The main difference is that in the process of Astanga-yoga, one has to execute a very difficult process, and usually he will be, at best, capable of achieving Paramatma realization, while a Bhakta can achieve complete Bhagavam realization, the final and ultimate level of transcendental realization by just becoming absorbed in Krsna’s name, form, pastimes, etc.

The stage of brahma-bhuta is described in the last chapter of the Bhagavad-Gita: “One who is thus transcendentally situated at once realizes the Supreme Brahman and becomes fully joyful. He never laments or desires to have anything. He is equally disposed toward every living entity. In that state, he attains pure devotional service unto Me.” (BG 18.54)

This is the goal of all processes of yoga. The very word yoga means “to connect” or in other words, bring one’s consciousness from matter to spirit, allowing him to connect with the divine. This connection is firmly established in this stage of Brahma-bhuta.

The stage of brahma-bhuta marks also the stage where one can start to practice a personal relationship with the Lord, in one of the five rasas cultivated in the spiritual realm. Some souls prefer the stage of neutrality, others prefer to serve the Lord, others cultivate a personal relationship on an equal level (friendship), others a paternal relationship, and others a conjugal relationship. Any of these rasas, or relationships, are possible for sincere souls, but they start from the stage of Brahma-bhuta, where one becomes free from material entanglement and thus is firmly situated in a pure, transcendental platform.