Srila Prabhupada mentioned that everything is inside his books. These are not just empty words, but the truth.

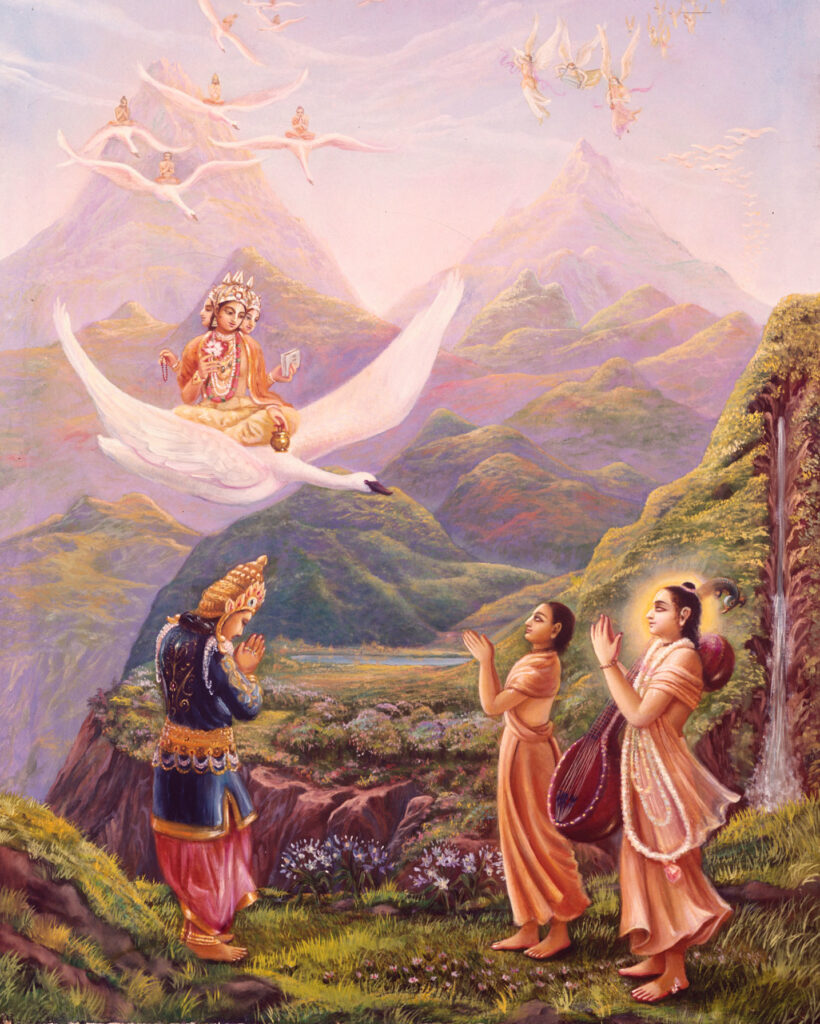

After compiling the four Vedas, Vyasadeva compiled the 108 Upanisads, making the spiritual knowledge contained in the Vedas more evident, culminating in the Vedanta Sutra, which brings forth the conclusions of the Upanisads. In the process, he also compiled the 18 Puranas, the Mahabharata, and other books.

Because the real meaning of the Vedanta Sutra is so difficult to understand, Srila Vyasadeva was instructed by his guru, Narada Muni to compile another book that would directly speak about the glories of devotional service and the pastimes of Krsna, making the real meaning of the Vedanta Sutra easily available.

By the time He received this instruction, Vyasadeva had already compiled the original Bhagavata Purana, as part of the 18 original Puranas, but having received this instruction he had the inspiration to rewrite the book as the Srimad Bhagavatam we have access to today. In this process, he received the help of two other great sages: His son, Sukadeva Goswami, and the son of Romaharshana, Suta Goswami, who added their realizations to the book, making it even sweeter than originally. The Srimad Bhagavatam was originally taught by Srila Vyasadeva to Sukadeva Goswami, who added His own realization while describing it to Maharaja Pariksit. This narration was later expanded by Srila Suta Goswami, resulting in the final text. This, in turn, was commented on by different Vaishnava acaryas, culminating with Srila Prabhupada, who compiled all this knowledge accumulated over thousands of years in his purports, adding his own realization in the process. This Srimad Bhagavatam we have access to is thus the fruit of the combined effort of all these powerful personalities.

The Srimad Bhagavatam is the authorized commentary on the Vedanta Sutra and is thus the ultimate conclusion of the Vedas. The philosophy of the Srimad Bhagavatam was then explained by Sri Caitanya Mahaprabhu, who made the ultimate conclusion of the text even more clear.

Srila Prabhupada explains that the Bhagavad-Gita is the ABCD of spirtual life, the Srimad Bhagavatam is the graduation, and the Caitanya Caritamrta is the post-graduation. We often think that the Caitanya Caritamrta is a book of pastimes, but if we read attentively the whole text, including all the purports we can see that it is extremely deep and has many philosophical details that are hard to understand. This is so because Srila Prabhupada wrote it for post-graduate students. The idea is that after studying the Srimad Bhagavatam we can deepen our spiritual realization by then studying the Caitanya Caritamrta.

In this way, Prabhupada books start from the basics (the Bhagavad-Gita and the smaller books), covering the intermediate level (the Srimad Bhagavatam) and the advanced level (the Caitanya Caritamrta). Everything one needs to return back to Godhead is contained there, therefore to say that Prabhupada’s books contain everything is not an exaggeration.

Another thing that Prabhupada offers us is a free Sanskrit master course, which is included in the form of the word-for-word translations of the verses. The main difficulty in learning Sanskrit is to learn the correct meaning of the words in different contexts, and this is exactly what Prabhupada gives in these word-for-word translations. If we study these word-for-words, we gradually learn the language. Srila Prabhupada once said that if one reads a chapter per day, including the word-for-words, one will become a Sanskrit scholar in 10 years. Many devotees in our movement who indeed became masters in Sanskrit started by doing just that.

Understanding Sanskrit may not be essential when we are studying Prabhupada’s books, because he makes everything easy to understand, but it becomes essential if one wants to later study other books, because practically all the translations available in the market contain mistakes, and often they completely change the meaning of the text. If one starts reading translations of different books and takes everything at face value, he will become seriously confused.

We hear that the Vedas are perfect knowledge and that everything that is written in the scriptures must be accepted. This is true when we read translations and purports written by Srila Prabhupada and other great acaryas, but when reading translations written by imperfect souls one has to have critical sense. Often one has to go to the Sanskrit to check what the verse really means, and then filter everything through the conclusions of the previous acaryas given by Srila Prabhupada in his books.

Just to give one example, see this translation of a passage from the Taittirīya Upaniṣad:

“The vessels of the heart named hitā proceeding from the heart, surround the great membrane (round the heart); thin as a hair divided into thousand parts and filled with the minute essence of various colours, of white, of black, of yellow, and of red. When the sleeping man sees no dreams so ever, he abides in these. Then he is absorbed in that prāṇa. Then speech enters into it with all names, sight enters into it with all forms, hearing enters into it with all sounds, the mind enters into it with all thoughts.”

It may not look like it, but this passage refers to the soul meeting Paramatma inside the heart when in deep sleep. When we enter into deep sleep, the functions of the senses stop and the soul takes shelter inside the heart, where Paramatma stays. Just like we merge into the body of Maha-Vishnu at the end of the creation, we take shelter in Paramatma at the end of each day. The point made is relatively simple, but the translation is completely unclear.

The writings of our previous acaryas are filled with references to the Upanisads and other books, for which there are no reliable translations available. As one progresses in his studies, some understanding of Sankrit becomes progressively more important, and thus this early training of attentively following the word-for-word translations Prabhupada gives becomes progressively more important.

I personally regret not having spent more time reading the word-for-word translations in the past.